The Hollowness of “Lethality” as a Benchmark for Military Policy

“Lethality” is a buzzword brought to the Department of Defense by former Secretary James Mattis (the last Senate-confirmed nominee), but it remains the all-purpose measure of military policy under the two (and counting) Acting Secretaries that have followed him.

Building a “more lethal force” is the theme of our National Defense Strategy. Throughout the chain of command, leaders include a salute to “lethality” at every opportunity. Perhaps the all-time winner in the category of worst references to lethality was the Chief of Naval Operations, who said that letting women wear their hair in a ponytail (not turned up in a bun) will make the Navy more lethal:

“All of this really is again to allow us one to be an inclusive team that is focused on being more lethal to our competitors, more lethal towards our rivals, our enemies and much more inclusive inside our team,” Richardson said in the broadcast.

The problem is that “lethality” as a measure of policy is meaningless. The concept is completely undefined, infinitely malleable, and outcome-determined, boiling down to this: “If I think it’s a good idea, then it increases lethality. If I think it’s a bad idea, it decreases lethality.” This is a completely reverse-engineered way of evaluating policy, and it can be used to justify any decision without accountability or explanation.

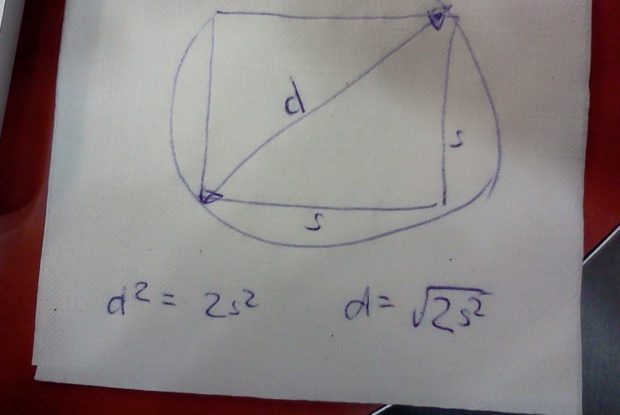

An article written by a Marine Corps logistician and a civilian applied mathematician, Quantifying Lethality on the Back of a Napkin, has exposed the empty sloganeering of using “lethality” to evaluate policy without any definition of what it means or any method to test its reliability. Since the Department of Defense appears intent on using “lethality” as a basis for policy development, the authors believe it must be defined and tested reliably:

“In order to make informed decisions with the goal of improving the lethality of its force, the United States needs to at least attempt to develop a rudimentary lethality metric that could be applied to comparatively analyze the impact of policies, equipment, operations, tactics and training.”

The authors propose a number of metrics to plug into calculations of lethality, such as size of forces in battle, military casualties, and civilian deaths. What’s fascinating about their method is that it can also apply rigorous analysis to “fuzzier” assertions about lethality, such as whether women in combat service reduce lethality. They compare two battles, one during the Korean War and one in Iraq, the latter including female combatants, finding little difference in lethality between the two:

“While far from conclusively demonstrating a broadly generalizable statement, the evidence here is contrary to the oft-trumpeted opinion that women reduce the lethality of units engaged in close combat and the squad remained combat-effective after this engagement.”

This raises a question of whether the military avoids defining and measuring lethality properly in order to avoid the answers it would provide. For just one example, the new transgender ban that went into effect in April 2019 was based on a report endorsed by former Secretary Mattis that used the term “lethality” over 30 times. Lethality was never defined; it was never measured; it was never tested. But the word was deployed repeatedly to assert that the presence of transgender people in military service reduces lethality. The Mattis Report was a 44-page version of “I think transgender military service is a bad idea, therefore I conclude it reduces lethality.”

Personnel policy is hard to measure on the basis of lethality because personnel policy is a constellation of trade-offs, although the authors of Quantifying Lethality on the Back of a Napkin show it may be possible.

Here’s one example from the medical rules for enlistment qualification. Under DOD Instruction 6130.03 (page 39), having high cholesterol is not a problem for enlistment, provided you don’t need to take more than one (!) cholesterol medication to control it. If we apply the “lethality” standard, does it make the military more lethal to enlist people who have high cholesterol and have to manage it with medication? Well, if you put it that way, no. But that’s not the point. The point is whether the military thinks the trade-off is worth the recruiting benefit.

Everything in accession standards is a trade-off. In a perfect world that doesn’t exist, we would want recruits who are intelligent, educated, motivated, moral and law-abiding, of sound judgment, and with no history of medical conditions and no future need for medical care. The military bends on every one of these hypothetical aspirations, making trade-offs that keep quality as high as possible while still getting (and keeping) enough people. You can’t look at any single trade-off and have a simple answer for the question, “Is this affecting lethality?”

This is especially problematic when DOD does not define, measure, or test the concept that it insists is so critically important to readiness. In the absence of better metrics, however, one thing that DOD could do is evaluate transgender persons by the same standards it uses to evaluate everyone else. Don’t disqualify transgender applicants for medical histories that would not disqualify others, and don’t discharge transgender members for medical needs that would not lead to discharge for anyone else. That’s an easy rule to apply.